36: Back to Business: Talisman Sugar

Pawley’s re-approval for covert activity in 1964 had a focus on the Miami business community. However, CIA documents about Pawley all but disappear for years. Even a review of his activities in the next decade assumed that his involvement with the agency ceased the same year his status was renewed: “Subject appears to have remained of interest to the WH Division and the DCI until as late as 1964.”1

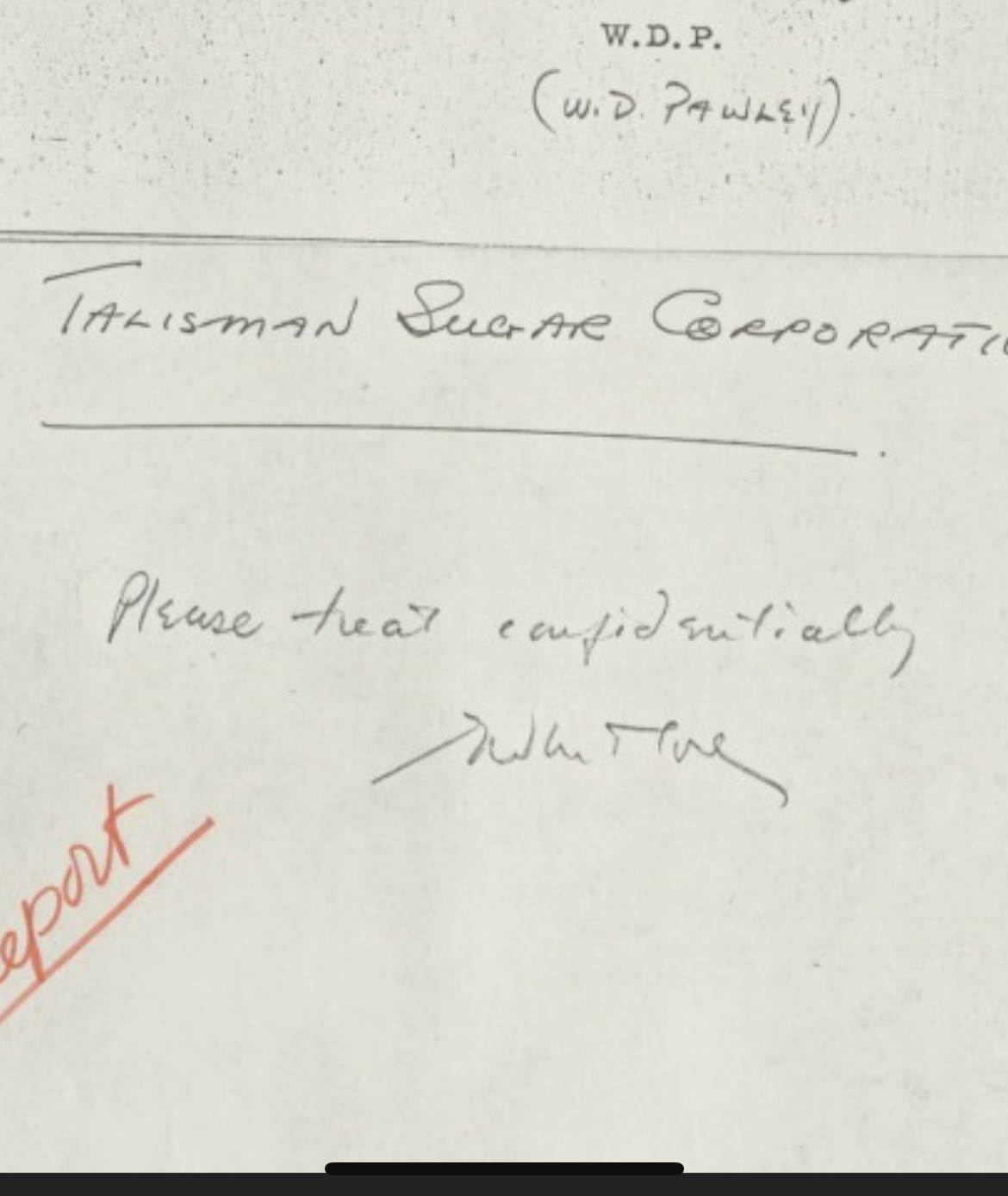

In that year, Pawley became president and chairman of Talisman Sugar Corp. in Belle Glade, Florida, which ranked among the largest private properties in Central Florida. As his manager of Talisman, he appointed Mike Cervera, a participant in the Bay of Pigs invasion.2 Talisman already employed a number of other opponents of Castro. The FBI looked into employees Angelito Goitia on October 16, 1961, and Octavio Ledon Baradania on December 11, 1962.3

Prior to Pawley taking control of the company, the Chief of Station of JMWAVE received a dispatch in September 1962 regarding Dr. Fernando De La Riva’s plan to organize “50 Cubans to come to Brazil [where Pawley had been Ambassador] to engage in anti-Castro activities ... De La Riva is owner or manager of the Talisman Company in Miami and also owns a part of Usina Baixa Grande sugar refining company located in Campos, Rio de Janeiro state ... De La Riva’s empire is associated with the Ford family’s financial interests.”4

The following year, FBI Special Agent Leman L. Stafford, Jr. reported on December 30, 1963, an interview with Jesus Sanchez-Martinez, an electrician at Talisman Sugar Mill, who claimed to have been invited along on a fishing trip from Miami Marine Stadium by Orlando Ramirez and Evelio Alpizar. When they got out to sea headed toward Cuba, U.S. Customs intercepted the boat and found bombs onboard.5

When Pawley took over the sugar company, he retained the Talisman name, which was a reference to the ancient Native American talisman that had been found near Belle Glade in 1933.6

On October 24, 1965, Tom Littlewood from the Chicago Sun Times reported on “The Sweet Job of Lobbying for a Wedge of Sugar Pie” noting that “Richard M. Nixon is registered lobbyist for a cane sugar-growing firm in Florida owned by William Pawley, ambassador to Brazil in the Truman administration.”7

On the seventh anniversary of the Bay of Pigs invasion, Pawley was mentioned in a Caribbean newspaper, not for his involvement in planning the failed operation, but for his leadership in the sugar industry. The Daily Gleaner of Kingston, Jamaica reported that Pawley, as head of Talisman, joined Ralph Lasbury of the Shade Tobacco Company, Fred Sikes of the United States Sugar Corporation, O. Wedgeworth of the Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association and others attended the annual meeting to “negotiate terms and conditions of employment” with employers of West Indian laborers. Pawley was said to be a tough negotiator on labor matters.8

In June 1968, the gossip column in a Waterloo, Iowa newspaper pointed out presidential candidate Richard Nixon was still lobbying for Talisman and for the American Bulk Carriers. The article also noted Pawley’s heavy financial backing of Nixon to be the 1968 Republican candidate over automobile lobbyist George Romney.9

On January 11, 1972, some two hundred drivers and field hands walked off the job at Talisman Sugar on U.S. Highway 27 in central Florida, in “the first strike by agricultural workers in Florida history.” The following month, it was reported that the farm workers union leader, Cesar Chavez, was now in Florida trying to organize migrant workers. Their “battleground continues to be the Talisman Sugar Corp., deep in Florida’s muckland country near the southern tip of Lake Okeechobee ... the company has refused recognition and continues to operate.” The article told of the death of college co-ed Nan Freeman who “was accidentally killed under the wheels of a sugar cane truck as she walked the picket line in support of the strikers in the predawn hours Jan. 25.” A “lawyer and two social workers attempting to talk to Jamaican sugarcane cutters inside Talisman property were arrested and charged with trespassing.” Caesar Chavez vowed to fight on with Talisman “‘until Mr. Pawley recognizes us.’” According to Chavez, Pawley who gets nearly $400,000 in farm subsidies was employing “black cane cutters” from the Caribbean to break the strike during the November-March harvesting season. They toiled 12 hours a day, every day of the week for $2 an hour, with no health benefits or overtime pay. Pawley “has refused any comment on the issue.”10

Pawley also denied that his plant supervisors carry guns or threaten workers who sympathize with the strikers. Only his labor camp manager who is a deputy sheriff carries one.11 His general manager, Cuban exile Miguel Cervera, claimed, “‘These people earn good money, especially considering what they do.’” The unskilled laborers made up to $200 a week for seven 12 1⁄2 hour days.12

In 1973, the Petersen v. Talisman Sugar Corporation case went to an Appeals court. The court record contains a description of Talisman’s workers camp which housed over a thousand workers, eight miles from the nearest highway and six miles from the nearest phone, which can only be used in an emergency.

Talisman Sugar Corporation, a sugar cane grower and producer, paid passage for approximately 1,000 Jamaican workers to work at and live on its sugar plantation from November, 1971 to March, 1972. The Jamaicans were hired under a contract complying with federal regulations and were brought to live in a camp near Belle Glade, Florida.

The camp consisted of housing for 1050 in the form of concrete block buildings. It had kitchen facilities, a mess hall, recreation facilities, a chapel, an infirmary, a laundry, and a store. Twice a week, the company brought in a minister to conduct religious services. In the store, it carried a general line of merchandise, including food and sundry items such as clothing. Traditionally municipal functions such as fire protection, sewage disposal, and garbage collection were handled by Talisman. There was a post office in the camp, but there was no public telephone of any kind. Though the company has telephones at its office some six miles from the camp which it allows anybody to use for an emergency, the workers cannot use these phones if they wish to make social or business calls. The camp is almost totally isolated from the outside world. There are either fences or canals completely surrounding the 38,000 acre tract upon which it is located. Eight miles from the nearest highway and six miles deeper into Talisman’s property than the sugar mill, the camp is twenty-five miles from South Bay, the nearest town. Four or five miles beyond South Bay lies the somewhat larger community of Belle Glade. Only one road leads from the camp to the highway, and this road is guarded by company employees. Though persons are admitted if brought to the camp on company business or if they come as friends or relatives of the migrant workers, Talisman has pursued a policy of excluding those it deems "inappropriate."13

Talisman soon attracted another investor whose wealth far exceeded Pawley’s. He was Edward Ball, brother-in-law of Alfred I. duPont—a descendant of one of America’s wealthiest families who died in 1935 and left a multimillion-dollar estate. Ball’s sister inherited Alfred’s fortune, and Edward Ball took control of it. The estate included holdings covering much of Florida, such as St. Joe Paper, and a partnership with Texas oilman H.L. Hunt in the Dallas Container Co.

While trustee for the estate, Ball built his power through his alignment with the northern Florida segregationist politicians known as the Pork Chop Gang and became famous for his toast, “Confusion to the enemy!” Pork Chop Gang member Mallory Horne was elected speaker of the Florida House in 1962. Mallory, a Democrat, outraged many members of his party when he posed with Republican former Democrat William Pawley “in support of Republican Barry Goldwater over Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential race.”14

Part of the fortune Ed Ball built was based on the Florida National Group of Banks which Congress forced him to sell after more than three decades of ownership. In 1966, William Pawley joined Florida National Bank & Trust Co. and became a director of the bank which had its Miami office in the Alfred I. duPont Building in Miami where Ambassador to Ireland Grant Stockdale had fallen to his death after the assassination of JFK. With the proceeds from the sale of the bank, Ball took control of Talisman Sugar in 1972, and “quickly made it profitable by replacing [Pawley’s] migrant workers with mechanized harvesters.” In 1976, later Ball purchased a sugar refinery from Borden.15 Pawley stepped down as CEO and Chairman that same year.16

As part of the celebration 50th anniversary of the Everglades National Park in 1997, the U.S. government purchased the Talisman property in an effort to enhance the natural environment while eliminating a major polluter.17

FOOTNOTES:

1 NARA104-100049-10208 ~ 4/30/1975 Memorandum for the Record. "Subject: William Douglas Pawley, SF#078 435."

2 Pawley, Russia Is Winning. Page 452.

3 NARA 124-90083-10045 ~ [No Title]. Subjects: Carlos Rodriguez Quesada, Denio Joaquin Francisco. From: MM. To: HQ. Pages 2 and 12.

>> Report of John E. McHugh dated October 16, 1961, at Miami. Will interview Angelito Goitia, contacted in care of Talisman Sugar Corporation with regard to fellow political refugee Dr. Odoardo Fonseca who went on to become a leader of the 30th of November Movement (see NARA 124-90083-10010).

HSCA Report, Volume III, Testimony of James J. Rowley refers to interviewing Octavio Ledon Baradania on December 11, 1962.

4 NARA 104-10512-10236 ~ 9/21, 1962. Dispatch: Anti-Castro Organization Planned for Brazil. Subject: GYROSE Anti-Castro Organization Planned for Brazil. From: Chief of Station, Rio de Janeiro. To: Chief of Station, JMWAVE.

5 NARA 124-10278-10412. [No Title]. Page 24 of 45.

6 “Welcome to Dike Okeechobee.” By Julie Hauserman, St. Petersburg Times, June 5, 2000 revision of May 31, 2000. http://www.sptimes.com/News/053100/Floridian/Welcome_to_Dike_Okeec.shtml

The mound builders near Belle Glade left ceremonial talismans: four-foot-high totem poles, hair pins carved from deer bones, daggers made from an alligator’s jaw, and a bowl made from a human skull. These were excavated by the Smithsonian Institution in 1933.

“Chavez's Farm Union Seeking to Organize Florida Citrus Workers,” By Jon Nordheimer. Special to The New York Times, February 7, 1972

7 “The Sweet Job of Lobbying for a Wedge of Sugar Pie.” By Tom Littlewood. Chicago Sun Times, Billings (Montana) Gazette, October 24, 1965. Page 4.

8 “U.S. employers of W.I. farmhands, RLB meeting here,” The Daily Gleaner, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies, April 17, 1968, Page 24.

Castro presented problems for some families. A November 13, 1968 letter was written to a CIA agent who had previously stated: “Dear Emmons [B. Brown], It was nice to talk to you again....Elana Carro is the ex-wife of Octavio Paz who, as you know, is the leading post of Mexico and who was until recently Ambassador to New Delhi....Elena and Octavio are, I understand, on very bad terms...personally and politically.” He pro-Castro; she pro- American and “wants help to get out of Mexico....All the best, A.”

9 “People Etc.” Waterloo (Iowa) Sunday Courier, June 2, 1968. Page 3.

10 “Chavez Claims Florida Victory,” Tri-City Herald (Pasco, Washington), February 6, 1972.

A college coed was accidentally killed under the wheels of a sugar cane truck as she walked the picket line in support of the strikers in the predawn hours Jan. 25. And this past week a UFWOC woman lawyer and two social workers attempting to talk to Jamaican sugarcane cutters inside Talisman property were arrested and charged with trespassing....

“Even if an agreement comes elsewhere, we’re not giving up on this fight with Talisman,” Chavez said in an interview. “We will be here from now on, until Mr. Pawley recognizes us.”

11 “Mill Supervisors Don’t Carry Guns, Plant Head Says,” Naples Daily News, February 1, 1972. Page 19.

12 “Citrus Growers Will Soon Recognize Farm Workers, Union Says,” Anderson Herald (Indiana), February 6, 1972. Page 12.

13 478 F.2d 73 Petersen v. Talisman Sugar Corporation.

478 F.2d 73

84 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2061, 72 Lab.Cas. P 13,960

Judith Ann PETERSEN et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

TALISMAN SUGAR CORPORATION et al., Defendants-Appellees.

http://www.openjurist.org

No. 72-2057.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

May 3, 1973.

Joseph C. Segor, Miami, Fla., Timothy Dyk, Washington, D. C., for plaintiffs-appellants.

William N. Lobel, Miami, Fla., Erle Phillips, Charles Kelso, Atlanta, Ga., for Talisman.

Kirk Sullivan, West Palm Beach, Fla., for Heidtman.

Before TUTTLE, WISDOM and SIMPSON, Circuit Judges.

TUTTLE, Circuit Judge:

1} Talisman Sugar Corporation, a sugar cane grower and producer, paid passage for approximately 1,000 Jamaican workers to work at and live on its sugar plantation from November, 1971 to March, 1972. The Jamaicans were hired under a contract complying with federal regulations,1 and were brought to live in a camp near Belle Glade, Florida.

2} The camp consisted of housing for 1050 in the form of concrete block buildings. It had kitchen facilities, a mess hall, recreation facilities, a chapel, an infirmary, a laundry, and a store. Twice a week, the company brought in a minister to conduct religious services. In the store, it carried a general line of merchandise, including food and sundry items such as clothing. Traditionally municipal functions such as fire protection, sewage disposal, and garbage collection were handled by Talisman. There was a post office in the camp, but there was no public telephone of any kind. Though the company has telephones at its office some six miles from the camp which it allows anybody to use for an emergency, the workers cannot use these phones if they wish to make social or business calls.

3} The camp is almost totally isolated from the outside world. There are either fences or canals completely surrounding the 38,000 acre tract upon which it is located. Eight miles from the nearest highway and six miles deeper into Talisman’s property than the sugar mill, the camp is twenty-five miles from South Bay, the nearest town. Four or five miles beyond South Bay lies the somewhat larger community of Belle Glade. Only one road leads from the camp to the highway, and this road is guarded by company employees. Though persons are admitted if brought to the camp on company business or if they come as friends or relatives of the migrant workers, Talisman has pursued a policy of excluding those it deems “inappropriate.”

4} Every other Saturday, the company furnished transportation to those workers wishing to go into the town of Belle Glade. The sole description of the town on these Saturdays was as follows:

5} “The streets . . . on Saturday might have half the population of Belle Glade on them . . . 12,000, 15,000 people, something like that; and heaven knows how many of this six to eight thousand Jamaicans that are employed by the various sugar companies are there.”

6} Due to lack of their own transport and the language barrier which confronted them in Belle Glade, as well as their limited financial resources, few Jamaicans left the camp except on these biweekly excursions.

7} In addition to the Jamaicans, Talisman employed domestic workers including field equipment operators. Some of these field equipment operators requested that Talisman recognize the International Association of Machinists as their bargaining representative. When Talisman refused, on the grounds that many other employees did not support the unionization drive, the field equipment operators struck. When Talisman hired strike replacements, the strikers began picketing the company’s property. Shortly thereafter, members of the United Farm Workers Union joined the picket lines outside Talisman’s plantation.

8} Plaintiff-appellants Judith Ann Petersen, Florida counsel to the UFW, David Hernandez, Associate Director of the UFW Ministry, a religious group, and Franklin P. Smith, a Methodist minister associated with the Florida Christian Migrant Ministry, sought to visit the Jamaican cane-cutters during the course of the UFW-Talisman dispute. Miss Petersen was seeking to substantiate reports that the company had been illegally using the Jamaican cane-cutters as field equipment operators.2 The other two named plaintiffs were supporting this inquiry and wished additionally to present the workers with information concerning their religious organizations.

9} On February 1, 1972, plaintiffs, accompanied by Father Kerry Robb, an Episcopalian minister, appeared at the entrance of Talisman’s property and requested permission to talk with the Jamaican workers in the labor camp. The gatekeeper, defendant Sergio De la Vega, informed them that they would not be permitted to enter without Talisman’s permission. After apparently placing a call, De la Vega told the plaintiffs that permission had been denied. Nevertheless, asserting a right to visit the workers in their living quarters, plaintiffs proceeded to drive down the access road toward the camp. Other employees of the company followed them and said that Talisman’s general manager, defendant Miguel Cervera, had forbidden them from entering the camp.

10} Plaintiffs thereupon returned to the main entrance and waited inside the gate on company property until a deputy of defendant William D. Heidtman, Sheriff of Palm Beach County, arrived. The deputy informed the plaintiffs that it was the policy of the Sheriff’s office to arrest persons trespassing on labor camp property after being warned off. He said he was acting pursuant to Florida Statute Sec. 821.01, F.S.A., which he read to the plaintiffs as follows:

11} “Whoever wilfully enters into the enclosed land and premises of another, or into any private residence, house, building or labor camp of another, which is occupied by the owner or his employees, being forbidden so to enter . . . shall be punished by imprisonment not exceeding six months, or by fine not exceeding one hundred dollars.”

12} Although the plaintiffs pointed out that the phrase “or labor camp” has been excised from the statute by the Florida Legislature in 1969, the deputy said that the protection given to “enclosed land” was enough, without more, to justify the arrest. The plaintiffs were arrested at this time, but no charges were pressed. However, after notice of appeal was filed in this case, an information was brought charging plaintiffs with trespass on Talisman’s property. The trial judge dismissed the charges on the ground that “to prevent their entry might lead to a condition where employees are subjected to a form of involuntary servitude, wherein the masters decide who may communicate with the servants.” State v. Petersen et al., Case No. 72M-8209, filed in the Small Claims-Magistrate Court, Criminal Division, in and for Palm Beach, Florida.

13} On February 7, 1972, plaintiffs instituted this class action in federal court, seeking a declaratory judgment and an injunction establishing the right of themselves and others similarly situated to visit the Talisman labor camp. Both compensatory and punitive damages were also sought against the defendants.3 Following a hearing on March 3, 1972, the district court entered an order dismissing the complaint. It held that Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 91 S.Ct. 746, 27 L.Ed.2d 669 (1971) barred relief, and that plaintiffs were not proper class representatives, had no right to access to the labor camp under the Sugar Act and the Wagner-Peyser Act, had no standing to assert First Amendment rights of the Jamaican workers to receive information, and had no right of access to the camp under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

14} Since the initiation of this suit, Talisman has spent over one million dollars on cane cutting machines, has given up its Labor Department certification for the importation of Jamaican workers, and has offered assurances that no workers will henceforth reside in the camp. The work force allegedly will be reduced permanently from 1,000 to 50 and the workers will commute except when there is reason to stay over. Though the buildings of the camp will not be destroyed, the services formerly provided will be discontinued. The gate will remain guarded, however, and access will continue to be granted only to those having direct business with the company or visiting employees “and those visits are desired by these employees.”

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

26}Contrary to plaintiffs’ contention, there is no evidence that Congress was primarily interested in the wages of domestic as opposed to foreign workers in cane fields when it enacted the Sugar Act. Nor have adequately-paid domestic employees hired by the same employer paying foreign employees at substandard levels been afforded protection under the regulations issued by the Secretary. The wage requirements apply with equal force to both foreign and domestic workers, 5 the employer is required to keep records demonstrating that “each worker has been paid in full,” 6 and that “any person who believes that he has not been paid in accordance with this part may file a wage claim.”

27} The basic objective of the Wagner-Peyser Act was to establish an interstate system for the recruiting and transfer of labor. 29 U.S.C. Sec. 49(b). As we said in Gomez v. Florida State Employment Service, 417 F.2d 569, at 571-572 (5 Cir. 1969), the act was also intended to protect employees who move around the country to meet the needs of employers who use federal resources to secure workers. To fulfill this Congressional intention, we held in Gomez that the statute impliedly created a private civil remedy exercisable by the migrants against employers and officials charged with protecting their interests. We noted that it would have been unthinkable that Congress, “obviously concerned with people, would have left the Secretary with only the sanction of cutting off funds to the state.” 417 F.2d at 576.

28} The principal beneficiaries of both these Acts, therefore, are the Jamaican migrants living in Talisman’s labor camp, not the UFW organizers seeking access to them. In order to rely upon these laws, the UFW would have had to show that access by them is required to effectuate the migrant workers’ statutory rights. No such showing has been made.

29}We conclude that plaintiffs had no statutory right of access under the Sugar Act or the Wagner-Peyser Act. We must, therefore, face the broader constitutional question posed by this litigation.

IV. FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHT OF ACCESS

30} The district court’s dismissal of this action was in part premised upon the theory that, even if the company were subject to First Amendment strictures, the plaintiffs were not proper parties to represent the alleged right of the migrant workers to receive information. The court did not consider the propriety of the plaintiffs asserting a First Amendment right to bring information to the migrants and enter into discussions with them. While we agree that the standing of the plaintiffs to assert the rights of the Jamaicans is far from clear, see Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301 at 307-308, 85 S.Ct. 1493, 14 L.Ed.2d 398 (concurring opinion), even if we ignore the divergence of interests discussed above we pretermit this question since in our view plaintiffs have standing on another ground.

31} Two cases reaching opposite conclusions on the merits are instructive on the question of the standing of a disseminator of information to sue to protect his own First Amendment rights. In Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141, 63 S.Ct. 862, 87 L.Ed. 1313 (1943), a city ordinance prohibiting persons from distributing handbills, circulars, or other advertisements door-to-door was held unconstitutional. The plaintiffs, accorded standing to question the ordinance’s conformity to the First Amendment, were disseminators of religious information who had been arrested for door-to-door soliciting. In Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U.S. 622, 71 S.Ct. 920, 95 L.Ed. 1233 (1951), in which an ordinance barring door-to-door commercial solicitation was upheld, the plaintiff magazine sales representative was held to have standing to assert his own right to distribute his wares although he could not represent the rights of housewives to receive his products. Similarly, the plaintiffs here have standing to sue as members of the public who have sought to communicate with the workers living on the company’s plantation.

32} Turning to the merits, we must decide (1) whether sufficient state action exists to subject Talisman to the restraints of the First Amendment and (2) if so, whether the company’s restraints on the rights of the plaintiffs to talk with the migrants were a reasonable exercise of its Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment property rights.

33} We begin with the proposition that “the First and Fourteenth Amendments safeguard the rights of free speech and assembly by limitations on state action, not on action by the owner of private property used nondiscriminatorily for private purposes only.” Lloyd Corp. v. Tanner, 407 U.S. 551, at 567, 92 S.Ct. 2219, at 2228, 33 L.Ed.2d 131 (1971). While a “special solicitude” has been shown for the guarantees of the First Amendment, the Supreme Court “has never held that a trespasser or an uninvited guest may exercise general rights of free speech on property privately owned and used nondiscriminatorily for private purposes only.” 407 U.S., at 568, 92 S.Ct. at 2228. However, neither is property insulated from the strictures of the First Amendment merely because it is owned by an individual or a company rather than a formally incorporated governmental unit. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 66 S.Ct. 276, 90 L.Ed. 265 (1946). Our inquiry, therefore, must be directed at whether or not Talisman Sugar Corporation occupies the shoes of the state for First Amendment purposes vis-à-vis these workers and the plaintiffs who seek access to them.

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

37} Like Chickasaw, the Talisman labor camp consisted of residential areas, streets, a store, eating facilities, a post office, and even a chapel. It was a self-contained community in which municipal services were afforded for a thousand migrants8 during the cane-cutting season, from fire protection and postal services to sewage, garbage disposal, and electric services.

38} The labor camp here is more closely analogous to the traditional “company town” than were the shopping centers in Amalgamated Food Employees Union v. Logan Valley Plaza ...

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

APPENDIX A

United States District Court

Southern District of Florida

48} Judith Ann Petersen, Franklin P. Smith and David Hernandez,

49} Plaintiffs,

50}versus No. 72-198-Civ-CF

51}Defendants.

52} Talisman Sugar Corporation, etc., William D. Pawley, Miguel Cervera, Sergio De la Vega, and William Heidtman, Sheriff of Palm Beach County, Florida,

53} Defendants.

ORDER

54} This cause came before the Court upon plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction. Although the Court was of the opinion that this cause was dismissable upon defendants’ motion to dismiss, out of an over-abundance of caution this matter was scheduled for a hearing upon plaintiffs' application for injunction, and upon stipulation of counsel, this cause was consolidated with the hearing of the injunction application and was fully tried on its merits as to all issues, except the claim for damages, at the time of the injunction hearing. Rule 65(a)(2), Fed.R.Civ.P.

55} This is an action brought by an attorney, employed by the United Farm Workers, AFL-CIO, a domestic farm labor union, and two ministers, one the associate director of the National Farm Worker’s Ministry and the other a staff member of the Florida Christian Migrant Ministry, on behalf of themselves and a purported class they represent. It is claimed by the plaintiffs that their purpose is to improve the economic and social conditions of agricultural workers and that their purpose has been frustrated by the defendants who have denied them free ingress and egress to the defendant Talisman’s labor camp to visit with, meet with, and interview certain Jamaican farm laborers.

56} The defendant Talisman Sugar Corporation is a Florida corporation engaged in the growing, processing, and sale of sugar cane. In its business Talisman employs agricultural workers, both domestic and foreign. Because there are no domestic farm workers available to fill certain of its available positions, specifically sugar cane cutting or harvesting, defendant Talisman employes foreign laborers pursuant to various federal statutes and regulations, including but not limited to the Wagner-Peyser Act, 29 U.S.C. Sec. 49 et seq. Defendant Pawley is the President of the defendant corporation; defendants Cervera and De la Vega are employees of Talisman. William Heidtman, Sheriff of Palm Beach County, Florida, has been joined as a defendant because he and his staff are authorized to enforce the various Florida criminal statutes, including Sec. 821.01, trespass after warning. At this time, members of the United Farm Workers who operate heavy equipment and machinery at Talisman Sugar Corporation are striking Talisman. Picketing outside Talisman has been occurring for some time.

57} This action has been brought pursuant to a multitude of Federal Statutes and United States Constitutional provisions. The jurisdictional bases which the plaintiffs allege for this action are as follows:

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

68} As stated, the plaintiffs claim that theirs is a charitable purpose-to aid the plight of agricultural workers, particularly, in this case, the imported, temporary Jamaican farm workers employed by Talisman, and that this purpose cannot be accomplished without the defendant Talisman permitting the plaintiff and others to freely come and go into the Talisman labor camp. It is claimed that various rights of the plaintiffs have been improperly denied by Talisman’s barring the plaintiffs’ entry upon Talisman land and by the Sheriff’s enforcement of Florida Statute Sec. 821.01, F.S.A., trespass with warning. It is further alleged that the Jamaican workers housed upon Talisman land are being enslaved and held in some sort of bondage or involuntary servitude by reason of Talisman’s refusal to permit entry onto Talisman land of the plaintiffs who wish to meet with the Jamaican workers.

69} This matter is alleged to be an emergency matter. It is alleged by the plaintiffs that they seek immediate entry into the Talisman camp so that they might “investigate” certain charges that the defendant Talisman has been utilizing the Jamaican laborers in jobs other than those for which they were brought to this country. The plaintiffs allege that it has been reported to them that the Jamaican laborers are performing jobs which were being performed by the striking farm workers-operation of farm equipment and machinery. The striking workers are members of the United Farm Workers. The plaintiffs wish to accomplish this investigation before the end of the harvesting season, because at the end thereof the foreign workers are sent back to their country. The season will end within a matter of days.

70} As stated, the plaintiff Petersen is counsel for the United Farm Workers, and one of the plaintiff ministers testified that 50 to 60 per cent of his time was spent advocating and furthering the cause of this union. Furthermore, the plaintiffs testified that they have participated in the ongoing picketing at Talisman, either by carrying pickets or by giving moral support and other aid to the picketers.

71} During the trial of this cause, it rapidly became clear that the plaintiffs’ purpose was and is not to help these foreign farm laborers. The investigation which the plaintiffs wish to conduct and the information they wish to obtain therefrom could not benefit the Jamaican workers. Assuming there have been violations of law in the assignment of jobs to the Jamaicans, and that has never been proven, such information could only detriment the Jamaicans. If it was found that Jamaicans were being used in unauthorized positions, the defendant Talisman would lose the right to employ these workers, and the workers would be immediately deported. All this would be of benefit to the United Farm Workers, which apparently wishes to man these Jamaican-held positions with their own union workers-at a higher wage, of course-or, alternatively, wishes to cause the defendant Talisman, against whom the union is already on strike, further economic hardship. But this would be of no benefit to the foreign agricultural workers. Furthermore, if the plaintiffs were truly concerned about the Jamaican farm workers’ welfare, it should not be a cause for their concern that these workers may be performing tasks easier than cutting sugar cane with a machete in a burned over field filled with snakes and rats.

72} Obviously, this case is nothing more than a tactic utilized by the union in an ongoing and heated labor dispute. This is not a suit brought to accomplish anything more than a result favorable to the union in this dispute. There has been no evidence to the contrary.

73} On the basis of these facts, the first and foremost question is the standing of the plaintiffs to bring this action. This is not a suit brought by the farm workers themselves such as Gomez v. Florida State Employment Service, 417 F.2d 569 (5th Cir. 1969). Plaintiffs allege, as one of the bases for jurisdiction in this case, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolition of slavery. But the plaintiffs are not persons affected by any sort of bondage. They have apparently asserted this Amendment only on behalf of the Jamaican workers employed by Talisman. None of the workers themselves have complained of enslavement, and there has been no showing whatsoever that these workers are serving in bondage or under conditions of involuntary servitude.

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

75} In this instance, it is clear that the plaintiffs have no personal stake in the rights of these Jamaican workers and may not rely on the Jamaicans’ alleged constitutional rights as a basis for this lawsuit. The plaintiffs have no standing to assert these rights.

76} As stated, the present objective of the plaintiffs is to gain access to these foreign workers to investigate whether these workers are performing non-authorized jobs contrary to the Wagner-Peyser Act, 29 U.S.C. Sec. 49 et seq., and the regulations thereunder. The plaintiffs, however, are not employees of any State, Federal, or Jamaican administrative agency authorized to conduct such investigations. Testimony given at the trial of this cause indicated that there are numerous agencies which regulate the employment of foreign laborers and, according to plaintiffs’ complaint, defendant Talisman’s business is highly regulated. Apparently, charges of violations of the Wagner- Peyser Act were filed with the appropriate State and Federal agencies and an administrative hearing was held with regard to these charges, but there has been no finding by any investigative body, nor at the administrative hearing of any such violations. Nor were any violations proved to this Court. Furthermore, there has been no showing that the plaintiffs have any right to conduct yet another investigation into this matter.

77} It is also claimed by the plaintiffs that Florida Statute Sec. 821.01, F.S.A., is not enforceable against the plaintiffs to prevent their entry into labor camp grounds. It is alleged that this is so because in 1969 the statute was amended and the words “labor camp” were deleted therefrom. Armed with this newly amended statute, the plaintiffs entered Talisman’s land, refused Talisman’s request to leave, refused repeated requests by the Sheriff to leave, and finally submitted themselves to arrest for trespassing.

78} The plaintiffs now seek a declaration from this Court that labor camps are no longer private property for the purposes of enforcing the Florida trespass laws. This is a Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 91 S.Ct. 746, 27 L.Ed.2d 669 (1971) situation. What the plaintiffs seek is an injunction of some sort of the state prosecution for trespass. The Court finds no reason why plaintiffs’ claim-that Sec. 821.01 does not apply to labor camps and entry thereon-could not be asserted in State Court as a defense to the trespass charges, however. [Document truncated by David Price Cannon.]

80} It would be difficult if not impossible to find any other parties with the same interests as these plaintiffs-being neither members of the United Farm Workers nor Jamaican laborers nor persons who truly wish to aid, comfort, and benefit the Jamaican workers. Thus, this is clearly not a proper class action nor, as stated, have plaintiffs laid a proper predicate to make it one.

81} Plaintiffs allege that they were deprived of certain constitutionally guaranteed rights; however, there has been no evidence to prove such claims. This suit is nothing more nor less than a labor dispute. The plaintiffs, on behalf of the United Farm Workers, are seeking here to use the civil rights laws and the First, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments to foster the Union’s cause.

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

83} The Court having found and concluded that the plaintiffs have no standing to maintain this case; and that upon the facts and the law the plaintiffs are not entitled to the relief sought, either pendente lite or permanently. It is thereupon

84} Ordered, adjudged and decreed that the complaint herein be and the same is hereby dismissed at the cost of and with prejudice to plaintiffs.

85} Done and ordered at West Palm Beach, Florida, this 10th day of March, 1972.

86} /s/ CHARLES B. FULTON

Chief Judge

87} cc: Joseph C. Segor, Esq.

88} Judith Ann Petersen, Esq.

Mershon, Sawyer, Johnston, Dunwody & Cole 89

Charles Kelso, Esq.

[Document truncated by D.P. Cannon.]

14 “Former lawmaker Democrat Mallory Horne dies at 84.” By Kris Hundley. St. Petersburg Times, May 1, 2009.

15 National Cyclopedia of American Biography, Volume 60. Page 215.

Who’s Who in Commerce and Industry, 1966-67. Page 1015.

Gerard Colby Zilg, DuPont: Behind The Nylon Curtain (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ) 1974. Pages 491-494.

16 Pawley, Russia Is Winning. Page 452.

17 “Big Sugar's Tough Stance Aids 'glades; Failure To Make Deal Gave U.S. Chance To Buy Land.” By David Beard and Antonio Fins. The Palm Beach Post, December 14, 1997.

Talisman had been on the market for a decade before the U.S. government purchased the land, because Flo-Sun, U.S. Sugar Corp. and the Sugar Cane Growers Corp. of Florida would not match the sale price.

On November 23, 2021, the Justice Department sued to block U.S. Sugar’s proposed acquisition of Imperial Sugar.

Labels: Bay of Pigs, Belle Glade, Cesar Chavez, Edward Ball, Florida, Lake Okeechobee, Nixon, Pawley, Romney, strike, Sugar, Talisman

<< Home